Simple Secrets of Family Communication

by Rhea Zakich

Locked within her own sounds of silence, a young mother found release in a “talk” game that soon transformed the lives of all around her, and has gone on to sell more than 4 million copies.

Locked within her own sounds of silence, a young mother found release in a “talk” game that soon transformed the lives of all around her, and has gone on to sell more than 4 million copies.

My doctor had discovered nodules on my vocal cords. “Your voice needs complete rest,” he cautioned. “It is imperative that you not speak for at least ten days. A month of silence would be even better.”

Impossible, I thought. The family can’t make it through the day without my coaxing and supervision.

Nevertheless, I began carrying a notebook in my pocket. When my husband, Dan, asked a question, I jotted down my answer and showed it to him. At mealtimes I scribbled comments on a sheet of paper and passed it around the table to him, and to our sons Darin, ten, and Dean, nine. It was a tedious process and it didn’t work. Within a week I was reduced to nodding my head to simple questions. My family and I were drifting apart.

“Your throat is not healing,” Dr. Jack E. Sinder informed me at my next visit. “The nodules must be surgically removed.” Two operations followed – in January and March 1969 – and I remained speechless all that time. Then Dr. Sinder told me that I faced yet another month of silence.

“I don’t want to alarm you,” he said. “But it’s possible the nodules will return.”

As I left the hospital, an awful fear overwhelmed me. What if I can never talk again?

That night, I paced the dark, silent house. I’d always felt close to my family. Now, I sensed a gulf between us. I had never confided my inner feelings to Dan, or talked with him about his hopes and fears. And did I really know my own boys?

I was desperate for my family’s understanding, and yet there was no way to communicate my need. Oh God, how did this happen? I wondered. How do people get this far apart? Please help me!

For the first time since I was a child, I began to cry. Thirty-five years of pent-up emotions poured out. I’d grown up in Akron, Ohio, the oldest daughter in a working-class family. My father’s hard life had taught him that only the strong survive. He never allowed me to cry or show fear.

Gradually, I lost touch with my feelings – and only now did I start to gain some sense of the uncommunicative person I’d become. We all spend so much time talking, I realized, but we never really communicate. Slowly, I could feel a change coming over me. I decided that even if I never spoke another word, I would find a way to share my feelings with my family.

During the next few days I thought of dozens of questions I wanted to ask Dan and the boys. Was Dan ever afraid? What did Darin want to be when he grew up? What four things are most important to Dean? I thought of things I wanted them to ask me. What made me happy? Angry? If I could live my life over, what would I change?

Then one evening I sat at the kitchen table with a stack of blank cards. On each I wrote a question. Some were serious: “What is your definition of love?” Others were lighthearted: “What do you like to do in your spare time?” By responding honestly, a person would reveal a lot about himself.

Before long, I had nearly 200 question cards stacked on the table. For a while, I just stared at them. What next? Then it hit me: a board game.

The game would be simple. Each player would roll the dice and advance a marker. The player could land on a space requiring an answer to a question card, or a space allowing a comment to another player. There would be no talking out of turn, no winners or losers, only sharing and communicating.

The next evening, Dan, the boys and I played the “Ungame.” During the first round, we drew lighthearted questions that let us talk about dream vacations, favorite foods and movie stars. When my turn came, I jotted down my answer and showed it to everyone. And they had no choice but to wait for me to finish and then read my response. I was elated. I felt as though I belonged again.

Later Dan drew a card that said: “Share something that you fear.” He was quiet a moment. “With your mother ill,” he said slowly, “I worry what will become of us. I don’t know if I could raise you boys alone if anything happened to her.”

I was astonished. My husband knew what it was like to feel frightened, to have self-doubts.

Darin, a bright student, drew the card that asked him to talk about success. “I hate it,” he said softly. “Everyone expects me to do the best. I always feel pressure.”

I shrank in my chair. I constantly push him to do better, I realized with guilt.

Then it was Dean’s turn. “How do you feel when someone laughs at you?” his card asked. “I want to die,” he said, staring at the floor. “It makes me feel stupid.” This time, his brother, a great teaser, blushed.

Around the table we went, sharing deep, private thoughts. “I’ve learned more about all of you in these twenty minutes than in the past five years,” Dan announced. “Let’s play again tomorrow.”

Through the Ungame, I developed new respect and understanding for Dan’s problems at work. I found myself being more patient with my sons. I even began to touch and hug them. In turn, they argued less. Dan talked more to all of us. We began taking Sunday drives and doing more things together.

One evening Dan invited our neighbors Joe and Alice to play the game, and they borrowed it to play with their kids. Their oldest son took it to his school psychology class, and his teacher asked for copies. Before I knew it I had begun a career as an amateur game producer.

I was calm as I returned to Dr. Sinder, ready to accept the verdict. When he pronounced me cured, I felt I’d been given a special gift. But I knew I’d never revert to my old speaking habits. Over those long months, I had learned five secrets of real communication:

1. Listen – just listen. One day during my enforced silence, Dean came home from school shouting, “I hate my teacher! I’m never going back to school again!”

Before my vocal-cord problems, I would have responded with my own outburst: “Of course you are, if I have to drag you there myself.” That afternoon I had to wait to see what would happen next.

In a few moments, my angry son put his head in my lap and poured out his heart. “Oh, Mom,” he said. “I had to give a report and I mispronounced a word. The teacher corrected me and all the kids laughed. I was so embarrassed.”

I wrapped my arms around him. He was quiet for a few minutes. Then suddenly he sprang out of my arms. “I’m supposed to meet Jimmy at his house. Thanks, Mom.”

My silence had made it possible for Dean to confide in me. He didn’t need advice or criticism. He was hurt. He needed someone to listen.

Silence taught me that the listener is the most important person in any conversation. Before I lost my voice, I never really paid attention to what anyone else was saying. I was usually too busy thinking of my response. Often I’d interrupt.

2. Don’t criticize or judge. As I was sitting with Jackie in her kitchen one afternoon, her 16-year-old daughter breezed into the house. “Hey, Mom, what do you think of abortion?”

Jackie turned pale. “I don’t ever want to hear you mention that word around here!” she shouted.

Why did Jackie’s daughter ask the question? Jackie may never know. And her daughter may never again try to discuss a serious or controversial topic with her. How often we parents, spouses or friends sabotage a conversation with quick comments or judgments.

Shortly after that incident, another teenager, Melissa, and her mother were playing the Ungame. When Melissa was asked to talk about an unhappy experience in her life, she related how sad she’d been when a close friend had an abortion. Like Jackie, Melissa’s mother was shocked, but according to the Ungame rules she couldn’t say anything until she landed on a comment space. “I didn’t think that things like abortion happened to girls in your school,” she said.

“You’d be surprised how many I know of,” Melissa replied quietly.

When the game ended, mother and daughter walked off together in intimate conversation. It was the first time Melissa had confided her fears about sex to her mother. “I didn’t realize we could have such a talk,” Melissa’s mother told me later.

To encourage your child or spouse to talk, check your negative reactions. Make a neutral statement such as, “I didn’t realize such things bothered you.” This opens the door to communication, rather than slamming it shut.

3. Talk from the heart. Several years ago, I was at a local park just as a neighborhood football game was ending.

“Hey, Dad, did you see me get the touchdown?” one ten year-old boy yelled proudly.

“How come you dropped the ball in the second quarter?” his father replied. “You need to practice your catching.”

I watched the boy slink along beside his father, his enthusiasm gone.

The boy had used what I call “heart-talk,” that is the language of feelings and emotions. Instead of sharing in his son’s happiness, the father had responded intellectually with “head-talk.” He meant well, but his response diminished the boy’s accomplishment. In the long run the boy would find it more difficult to ask his father for help.

4. Don’t assume. Many people have preconceived notions about their spouses or children that hamper communication. Don’t assume that you know another person’s thoughts or feelings.

Doug and Mary had been playing the Ungame for about 30 minutes. Mary drew a card that asked if she ever felt lonely. “I feel lonely every night,” she whispered. Her husband blushed. After the game ended, Doug confronted her, “How could you say that?”

“Every night when we’re in bed,” Mary said quietly, “you turn your back to me.”

Doug’s mouth fell open. “I broke several ribs playing high school football and they never healed properly. I turn over so I can sleep on the side that doesn’t hurt.”

Two weeks later, I bumped into Doug and Mary at the supermarket. “We solved our problem.” Mary told me. “We changed sides of the bed.”

5. Show your love. Actions can be as important as words. One evening, I played the Ungame with Carmen, her husband and two children. Carmen was 43, attractive and financially well-off. Here’s a woman who has almost everything, I thought.

Carmen drew a card that asked her to talk about a hurtful moment. “When I was six,” she revealed to her family for the first time, “my mother told me I was too old to be kissed. I felt so bad, that every morning I went into the bathroom and looked for the tissue on which she’d blotted her lipstick. I carried it with me all day. Whenever I wanted a kiss, I rubbed the smear of lipstick against my cheek.”

Carmen’s life had not been as perfect as I’d thought. For almost 40 years, she had endured this small, private heartache. Can anyone ever make up for that? I wondered. Several turns later, Carmen’s eight-year-old son landed on a comment space. Quietly, he got up and walked over to his mother. Without a word, he put his thin arms around her neck and kissed her on the cheek. Carmen’s eyes filled with tears. The old hurt was gone – perhaps for good.

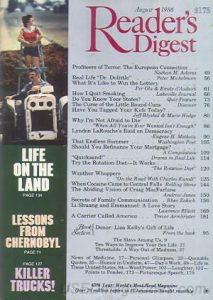

This article appeared in the August 1986 Reader’s Digest when the Ungame was at its peak of popularity. I had been traveling to 26 cities across the United States for the Ungame Company. In each city, I was on radio and TV shows telling the story of how I created the game and what it was doing in the lives of people around the world.

While in Chicago, there was a terrible snowstorm and all of my appointments were canceled, except one. A reporter for the Chicago Tribune happened to be living near the hotel where I was staying. She called and asked if she could interview me in my hotel room. We spent 3 hours together and the next day I flew home without knowing what would become of her work. The 30 hours in Chicago seemed to be a waste of time.

Several months later I received a phone call from a woman who said she saw the great story in the Tribune and would LOVE to help me write an article to submit to the Digest. I asked her what was involved and she said, “I’d like to come and live with you for one week to get to know you and see you in action.” (The Tribune article mentioned the Communication Workshops and Classes I had been leading.)

I agreed and in a few weeks, she arrived. From morning until night, she questioned me (about everything) and went everywhere with me. During that week I met with several groups that played the Ungame. When she went home, she had 65 audio tapes that she intended to process to find the best story. (She said there were several stories that the Digest might be interested in.)

Nearly a year passed and I was sure nothing would come of our time together. Then the day came when she called me and said she had transcribed the hours of tapes and created 4 possible stories. The Digest was interested in the “Family Communication” story. (I had hoped that it would be my “Faith Story” but she said they had their story of faith for the next three issues.) Within a few days, I received about 100 typed pages of my story told in my own words. Together, in the next 2 weeks, we condensed it down to 5 pages. It was a difficult process and most of the credit goes to Pat Skalka, the writer from Chicago, even though my name appeared on the article.

Reprinted with permission from the August 1986 Reader’s Digest. © The Reader’s Digest Association